Design Older Than Digital

While we at Fuzzy Math focus on the digital side of user experience, UX as a discipline has always been concerned with how humans interact with any environment or tools that they use — from the principles of Feng Sui to Hippocrates illustrating how to best set up a surgery theater here:

“One must also consider the surgeon’s position in relation to the point of operation, that is whether he is close or far, at a higher or lower plane, to left right or at the center…As regards the tools, we will state how and when they should be used; they must be positioned in such a way as to not obstruct the surgeon, and also be within easy reach when required”

This sounds like UX to me.

In my experience, when being introduced to UX design, you often consider the field as quite new and very fixated around a digital screen. However, UX in various forms has been around for generations, and it’s fun to explore the fact that human beings have always taken the time to make sure their tools and environments are suitable for humans.

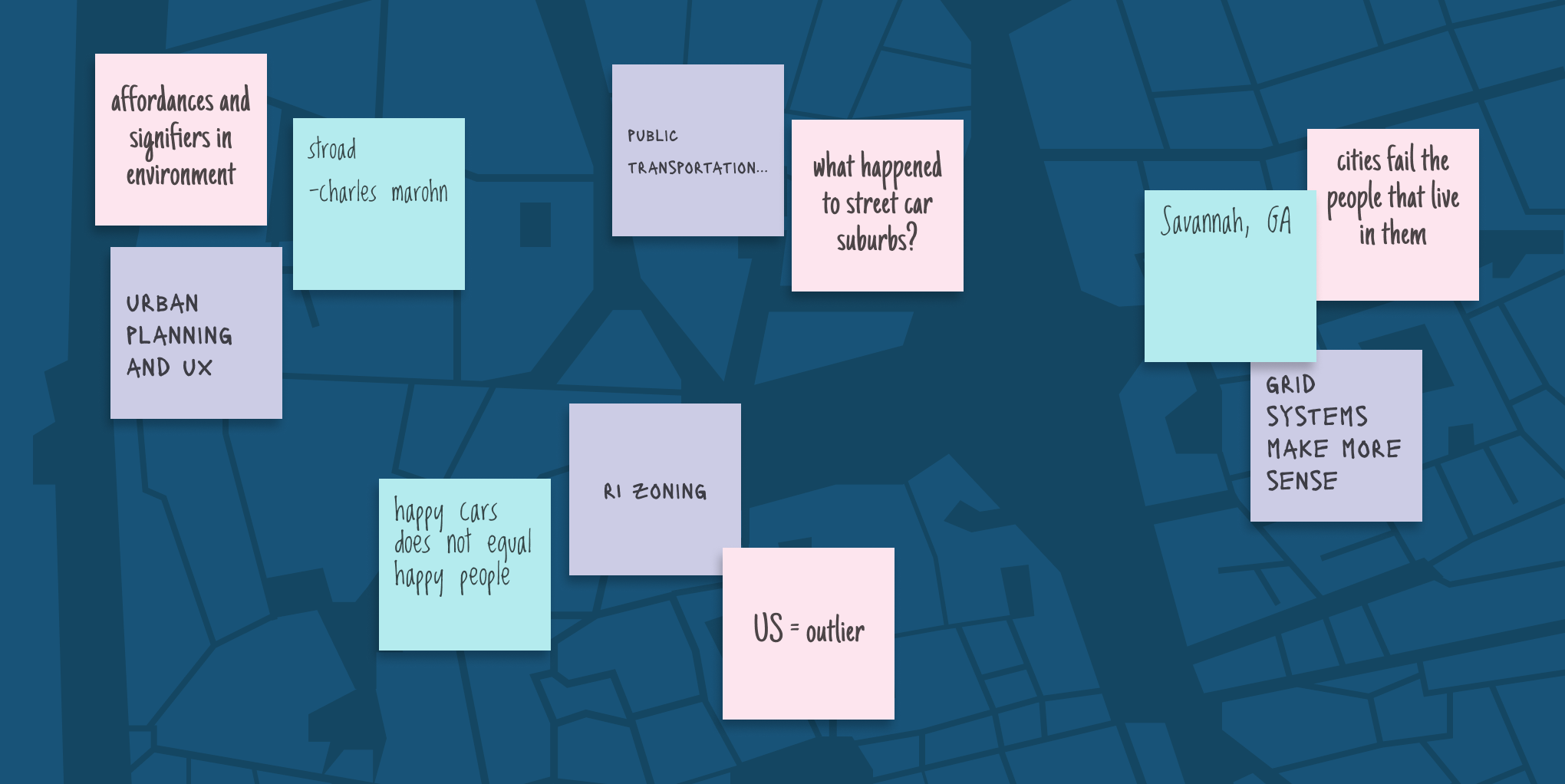

I intend to focus here on the intersection between UX and Urban Design — how things familiar in the digital design world can be (and are being) translated into real, lived environments and are being leveraged to make greener, sustainable, and (very importantly) livable cities.

Using ‘affordance’ in order to make cities for people

Affordance is an important element to all digital design — it’s why a user understands that they can interact with a bit of text that’s colored blue and underlined (like how you may or may not have clicked on the word affordance at the beginning of this paragraph).

The blue and the underline are both signifiers letting a user know that the bit of text is interactive, and the text itself gives the user a clue that interacting with this will most probably take them to a page that explains affordance.

Affordances are essential elements of digital design but how might they play a role in designing better, more livable cities and towns?

Affordances in an urban design capacity means looking at what a physical space affords the people in it. It examines the complex relationship between people and their material environments.

Using this, it’s possible for designers to ask whether a space affords for human needs. The need for safety? The need for socializing and a feeling of belonging? The need for a sense of diversity and beauty?

In order to talk about this, I want to give an example of a planned environment that was not planned for people, unless they are in a car (and even then it is still bad). It takes the human need for safety, greenery, and belonging and throws them out the car window. It’s called a stroad.

Most people, especially those living in cities and towns in the USA or Canada will be familiar with a stroad (by sight if not the name). Stroad is a portmanteau of ‘street’ and ‘road’ and was coined by an urban planner named Charles Marohn.

It is argued by Marohn (and a growing number of designers, engineers, planners, and enthusiasts) that urban design like this is dangerous, ugly, and terribly inefficient. The stroad is likened to a futon — something that tries to be a bed and a couch, but manages to be uncomfortable to use in both roles.

The Difference Between Street and Road, and How ‘Stroads’ Fail

A street is meant to be a place where people, whether they are on foot, on a bike, or in a car, can easily interact with businesses, services, and public spaces. This easy interaction allows communities to grow, and businesses and services within them to flourish. A road is meant to be an extremely efficient route between two places. Combining them, as has been done in almost every city in the US, is a recipe for disaster and only serves to make a “hideous, inefficient, and disposable environment that quickly loses value.”

When looking at it through the lens of affordance, as we talked about earlier, urban design like this fails on nearly every level. They do not provide safety, even for those for whom they were explicitly designed for – people in cars. They are, however, especially unsafe for pedestrians. They are objectively ugly places. I challenge you to find a person who sincerely thinks miles of asphalt parking lots and fast food signage is aesthetically pleasing. And finally, by their nature of serving cars only, they are incapable of building community — there are no public spaces here, it is people going from their single family home, to their single family car, to a store where their interactions with others will be curt at best.

If you are a pedestrian in the space in the picture above, what are your affordances? How can you interact with this environment? Where can you go and what can you do? It will be hard to walk, as there are typically no sidewalks present in these areas. If you want to go into one of the stores, you will have to use the curb of an intersection to climb up into a massive, sweltering parking lot which you will need to cross. If you want to go to a store across the stroad, good luck, because often even if there are stop lights, there are no crosswalks or signaling to let you know how much time you have.

A Better Direction

These things can be reversed and designed through the lens of affordances to provide for human friendly spaces. You can see below an example of a stroad (though not the worst type of stroad) was redesigned to be a space that people might want to be in, there are new crosswalks, yield signs, foliage, bike lanes, a roundabout to slow traffic, and widened sidewalks and outdoor spaces. It’s an example of what more human centered design can accomplish.

The Root(s) of the problem

We explored the stroad, but stroads aren’t the problem, they’re a symptom of the problem. The problem being that, in the words of renowned urban designer Jan Gehl, “the main focus [of urban planning] has been to keep the cars happy”.

Making cars happy, however, is not the same thing as making people happy. For example, another symptom of this alongside stroads, is that – even in the urban areas in the US – parking lots dominate the landscape.

Pave Paradise and Put Up a Parking Lot

Parking is a perfect example of another symptom of the problem that has huge ramifications for the environment and the people living in it.

Parking is costly, environmentally unfriendly, ugly, and has deleterious effects on community and walkability. It is also EVERYWHERE. In LA, a city undergoing a massive housing crisis, parking stalls account for more space than actual housing.

Above is downtown Peoria, Illinois — a city that was once thriving, as many ‘rust belt’ communities were — and is now taken over by unfriendly urban design. The red in the picture are the parking lots found in the downtown. You can also notice a bonus unfortunate design choice caused by favoring cars over people in the above picture — in the top right you can see the large segment of street that is interstate 74, a highway cutting through downtown which separates communities and makes traversal on foot or bike far harder.

The next time you’re in a town or city, or even driving along a stroad, take a moment to take in just how many parking lots there are, and how much more space they take up than the footprints of the buildings around them.

The UX of It All

Where does UX fit into all this? Well, if there is something that UX design, and UX designers excel at, it is digging at the base of problems to find their roots. A big part of the profession is being able to manage or dispel the fantasies of stakeholders in a project and to advocate for the users, the human beings that will be impacted by or using the project on a daily basis. This is what urban designers must also do, but it is arguably harder because not only are the budgets involved usually far higher, but the time spans for a project are measured, usually, in decades.

In good UX design fashion, for the rest of this post, I will endeavor to dig into some of the root problems of what I’ve described above and postulate some potential solutions.

Zoning

There is an overabundance of single-family detached homes in the US. This type of zoning (often referred to as R1 zoning) is what you’d imagine your typical, sprawling suburban landscape in the US to look like. It is my contention that this type of zoning is wildly inefficient, spurs inequality and housing shortages, and (what I’ll focus the most on) yokes vast swathes of the population to auto dependence with few other options.

I want to say, before starting in earnest, that single family zoning in the US has a racist history. Many neighborhoods in the US were built and zoned to enforce racial segregation. Because this fact is so related to what is being discussed, it needs to be mentioned, however, I do not think that I am qualified to give that particularly nasty element of US urban planning history the nuance and care it deserves. There are others who have tackled this topic far better than I could.

R1 zoning, like parking lots, is everywhere in the US. It is estimated that 70% of the zoning in LA is R1, 80% in Seattle, and 90% in San Jose.

The US is an Outlier

The US is a complete outlier when it comes to zoning for this type of development. Many countries have single-family detached homes, but the zoning in those places specifically allows for other types of development. Shops in the fronts of homes, higher density homes that cost less, commercial and recreational green space mixed with residential. Many places in Japan, the Netherlands, even in rural areas, have mixed density zoning. Much of the zoning in the US makes this type of mixed development impossible. R1 zoning takes up so much space, and is so unaffordable, but for many, it is the only option.

Why is this important and what’s the problem with single family homes?

There isn’t an inherent problem with single-family homes (other than often prohibitive cost, for which there are solutions). The problem is with not allowing anything else. Not allowing anything else causes massive amounts of sprawl, encourages developers to bulldoze ecosystems and productive arable land to make ever more room for single-family houses, and causes more and longer trips by car as there is often no public transport in suburban or rural areas.

Keeping these areas unaffordable also has social consequences because:

Where people live has a dramatic impact on their lives. “It determines their exposure to pollutants and violence, their access to good schools for their kids, and what jobs they can reach. Residential location is thus strongly correlated with many life outcomes”

The solution is to end R1 zoning, and embrace up-zoning. Start building denser, more affordable developments in previously R1-zoned areas. This will encourage homeownership for more income levels, which in turn will encourage investment in the community. Start allowing for small businesses in the same areas as residential, which will allow people to shop for their needs without a 15-minute car trip to Target, which will reduce cars on the road and promote walkable, accessible neighborhoods where people know, and hopefully begin to care more for each other. This last bit might seem ‘pie in the sky’ but we humans are a social animal, and strong communities (which isn’t the same as a lack of privacy) is good for our wellbeing.

Grid Systems and UX

In digital design, we are often very concerned with the framework of a platform or service, how is it laid out and how will someone navigate it? We have mentioned how important things like information architecture and navigation are to both digital UX design, and UI design.

The requirements for good user experience, and the design of frameworks, architecture (of course), and navigation can be very similar in the design of urban areas. Similar things like learnability, trustworthiness, accessibility, and satisfaction have to be taken into account.

However, there is a big difference for some cities in that many were built with absolutely no framework, or navigation concepts in mind at all. Many cities around the world grew organically around a water source and a nice patch of grass – this worked very well until entire populations began moving into cities and their suburbs en masse.

This is where the profession of urban design sprang from and where city plans like those of Chicago, Philadelphia, and very famously, Savannah came from. Orderly grid systems that encouraged (and still do despite the changes made to accommodate cars) walkability, community, and plans for future growth. The shorter distances between intersections (in most gridded cities, looking at you Salt Lake City), and narrower streets encourage cars to slow down, which makes pedestrians safer.

Just like a well-thought-out navigation structure can help someone navigate through, and feel satisfaction using a digital product, so too can taking those same things into account in a city help someone feel a part of a community, and like they can get around with ease in their city.

Public Transportation

The last solution given was to work on upzoning all of the R1 lands that rings almost every American city for miles and miles. But that upzoning is only one step toward achieving an end to the stated problem — that our communities were designed to make cars happy — not people.

We at Fuzzy Math have spoken to the frustration of the more micro aspects of designs related to public transport right here in Chicago. Considering this is incredibly important as it impacts the daily commute of 300,000 people. But for this, as with the rest of the article, we’re considering the macro side of public transit.

The next, most important step, in my opinion, is to reduce the number of cars, and people’s dependence on them. There’s nothing better at doing that than building public transportation networks!

Connect the communities mentioned in the rest of the article to each other, and to urban cores, and then out into more rural communities.

Streetcar Suburbs

And no, I’m not talking about one or two Greyhound buses picking passengers up from a desiccated, poorly lit, abandoned TruValue parking lot. I’m talking about re-embracing things like streetcar suburbs. Many communities in the US before and during the rise of the car were serviced by a fan of streetcar lines that could take you anywhere.

The demise of the streetcar in the US was a multifaceted problem — namely, the violent, strikebreaking owners of the streetcar companies were unable to financially handle the contracts they signed which forced them to keep costs low while still maintaining the roads (being now destroyed by constant auto traffic). The streetcars began to face problems, and no one saved them — and by the 1950s the government was all too happy to funnel massive amounts of funds into oil, gas, and rubber industries to help car manufacturers, while at the same time, carving into the country, and often through cities to build our massive interstate highways. Of course, this situation also massively hindered the growth of our subways, busses, and passenger rail – to the detriment of everyone except GM.

In the sections before this, I essentially advocated for bringing the designs of both cities, and suburban communities back to the design of these streetcar suburbs. These places had narrower streets to reduce traffic speeds and provide tree canopy over residential streets. They were often planned and gridded for easier laying of tracks. They allowed for mixed development, and even for small commercial spaces in neighborhoods, allowing for walkability, and they connected everything with streetcars.

Above is an example of what I’m talking about, LA and London have a similar number of inhabitants and California’s GDP surpassed that of the UK in 2018, and despite GDP not being everything, I feel like California could probably do a bit better.

Imagine living in a place where you could have the space and privacy of a rural area, with access to the flourishing community, job opportunities, and civic spaces of a more urban area. You’d have a walkable neighborhood, filled with greenery, you’d have a well-funded and maintained streetcar that could take you into the neighborhood where you’d be connected to the well-funded and maintained train line that would take you into the city, where you’d be connected with the well funded and maintained subway that would take you anywhere else you’d need to go. You wouldn’t have to worry about your car, or where to park.

In Summary

We as digital UX designers, love to consider these challenges and look at what is going on in other fields of design as there are often interesting overlaps.

Similar to how a digital product can be designed for the wrong set of users, our urban areas in the US are far too focused on the individuality of the car and, as a result, are failing the communities that live in them.

This could be taken back to digital UX in any number of ways — a B2B design that’s focused only on the salespeople to the detriment of all other users. Or less specifically, designers prioritizing the need for a fast turnaround over the needs of accessibility and trustworthiness in the same way urban designers in many areas have caved to the pressure of clearing space and priority for Walmart over walkability, the environment, and safety. In the end, it not only hurts the people that use the product or travel the area, but it hurts the product and the area too.

Sources

- Hippocrates, Kat’ Ihtreion (About the hospital) – http://ergou.simor.ntua.gr/research/ancientGreece/AncientGreece.htm

- Sarah Goodyear, Bloomberg – https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-01-07/defining-the-worst-type-of-street-design

- Ryan Briggs, WHYY PBS NPR – https://whyy.org/articles/study-city-driving-often-safer-than-the-burbs/

- Adam Snider, Governors Highway Safety Association – https://www.ghsa.org/resources/news-releases/GHSA/Ped-Spotlight-Addendum21

- Ellie Violet Bramley, The Guardian – theguardian.com/cities/2014/dec/08/jan-gehl-make-cities-liveable-urban-rethinker

- Better Institutions, Parking Lot Study – http://www.betterinstitutions.com/blog/2016/1/2/map-a-parking-lot-with-all-of-la-countys-186-million-parking-spaces

- Rayla Bellis, Smart Transport Initiative – https://ssti.us/2020/02/24/the-argument-for-ending-single-family-zoning/

- Megan Campbell, Crossfire KM – https://www.crossfirekm.org/articles/the-more-the-merrier-a-case-against-r1-zoning-laws

- Manville, Monkkonen, and Lens, Taylor & Francis Online –https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01944363.2019.1651216