A cornerstone of Fuzzy Math’s user-centered design process is understanding our users through research. In some cases, remote interviews and screen shares don’t quite cut it — in order to really get the insights we need, we need to do ethnographic research and observe people in the real contexts that we’re designing for. Ethnographic research in design has some unique challenges but ultimately rewards us with highly applicable insights.

Here we explore five times that ethnographic research helped to drive effective design at Fuzzy Math and share our expert tips for conducting your own research in the field.

What is Ethnographic Research?

Put simply, ethnographic research (or ethnography) describes UX research that is observational and done in context. Just as an anthropologist travels to observe and participate in another culture, a UX designer or researcher conducting ethnographic research puts themselves right next to their user, observing their process and seeking to understand the entire ecosystem in which that process takes place.

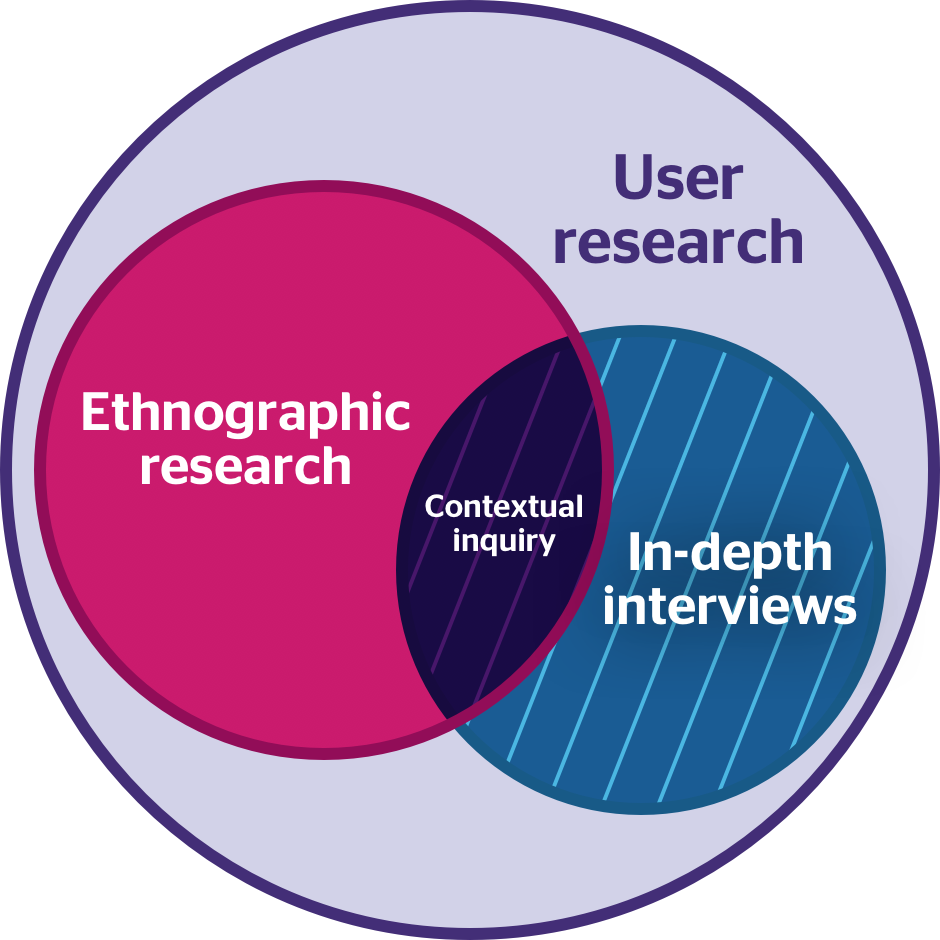

The majority of user research done at Fuzzy Math is a combination of ethnographic research and in-depth interviews that we refer to as “contextual inquiry.” This type of research allows us to observe the participant as they complete tasks in their typical environment while also asking questions to better understand how and why they’re doing what they are.

Need some help understanding your users? Ethnographic research is a core component of what we do at Fuzzy Math.

• • •

As we conduct ethnographic research across many industries and contexts, we hope that some of our experiences and tips below might help inspire you to conduct some ethnographic research of your own.

5 Examples of Ethnographic Research in Design

1. In-Home Tax Research

Anthropologist Margaret Mead once said that “what people say, what people do, and what people say they do are entirely different things.” So in doing research for how people file their taxes, we needed to actually watch them file their taxes. We asked people to meet us in person in their homes (or offices, or a cafe) to watch them file their taxes in whatever context they normally did them.

What We Did

Fuzzy Mathletes went in pairs to meet people wherever they were planning to file their taxes. We began each session with a few questions about the tax process and their previous experiences with it, and then watched participants as they filed their taxes, asking some questions along the way to gain additional thoughts and details during the task. We asked about everything from whether and why someone chose different software each year to how taxes made them feel and what the best and worst parts of the process were for them. During each session, we used physical artifacts — printouts with timelines and a Likert scale to measure their comfort level with filing their taxes — to supplement our conversations; we filled them out while asking participants to confirm what we wrote, and we asked follow-up questions spurred by the content created during the research.

Tips for Success

Creating artifacts like printouts to help ground conversations and to reference during an interview is useful not only during the interview but also to reference during analysis. For the parts of the interview relevant to the printouts (e.g. we took notes on a timeline about the tax process throughout the year), it was easy to go back and find similarities and differences between people’s processes in a relatively standardized format, rather than trying to dig through pages of notes for each of the 20 interviews.

What people say, what people do, and what people say they do are entirely different things.

2. Warehouse Research for a Grocery Distributor

We visited a warehouse for a national grocery distributor to talk to the workers on the ground managing products arriving into the warehouse. Our end goal: to redesign the process of tracking discrepancies between what was ordered from the vendor and what made it to the warehouse.

What We Did

Because the process at the time was done entirely between paper forms and a handheld scanner connected directly to their warehouse management system, remote research simply was not an option. We spent time early in the project doing ethnographic research and observing the receiving team as they worked on the warehouse floor trying to get products off the dock and put away as quickly as possible. This gave us a pretty good feel for the process of unpacking, counting boxes, doing math on the sides of boxes and in the margins of packing slips, and constantly stopping to scribble notes about any problems with the shipment.

Both of these user groups in the warehouse had their attention pulled in 10 different directions at all times. Because we had first-hand knowledge of what their environment was like, we were able to effectively advocate for their needs — increasing time spent on the computer does not make sense for these users.

Tips for Success

The shipping industry is beholden to the whims of Mother Nature, and there were times when our scheduled ethnographic research couldn’t take place simply because the workers were not able to do their typical jobs as ice storms kept trucks out of the receiving dock. During those sessions, having a backup plan was crucial. Prior to arriving we prepared a rough outline of interview questions that we could ask both receivers and clerks so that even when our ethnographic research fell through, our trip was still valuable.

We were also fortunate enough to have access to a warehouse near our home base in Chicago that allowed us to do our ethnographic research at multiple stages of the project. This means that we were able to return to follow up on processes we had talked about but hadn’t seen ourselves. However, this is not always the case, and you should always have a backup plan in place in the event that you are not able to conduct the research you expected.

3. Fraud Analysis Call Center Research

There’s a whole group of people out there whose job it is to make sure that travel bookings are legitimate. They determine whether or not it makes sense that this person is booking this hotel in Abu Dhabi or that flight to Iceland. Fuzzy Math was brought in to redesign their fraud analysis software with the goal of helping the fraud analysts connect the dots between a variety of data points in order to help them quickly identify fraudulent transactions.

What We Did

Not knowing much about this space, we embarked on a two-day on-site research trip that included both in-context observation and interviews with junior and senior users of the current fraud analysis tool.

There were several challenges that presented during our on-site research. First was the layout of the room in which these users worked. There were a lot of people, all of whom were constantly on the phone with hotels and credit card companies trying to confirm the information they had in front of them. This hectic environment made one-on-one conversation difficult, so our team relied on observation, watching users dissect the information and piece it back together in a way that made sense.

In-person observation also allowed us to see parts of users’ workflows that was taking place outside of the tool. This included supporting information like notes on jargon, phonetic alphabet codes, and codes for common processes and errors that were taped to computer monitors. We also saw that users were going out of the tool to take notes because the process of taking notes in the tool took them out of their current workflow, yet notes were required in order to finalize any decision.

Tips for Success

Taking the time to debrief after each session allowed us to adjust as we went to make sure we were getting a good understanding of the product’s use across the board.

Being on-site, we had the opportunity to observe training, which was incredibly useful in gaining an understanding of how the tool was being used and the very real workarounds for common errors that are communicated from one generation of workers to the next. When observing training, be sure to ask questions of both the expert trainer as well as the new user in order to get multiple perspectives within one setting.

By observing how new users are being trained to use a specific tool, researchers may gain insight into the very real workarounds for common errors that are communicated from one generation of workers to the next.

Take note of the users’ environment. What notes are they taking? What notes do they keep in eyesight? These may give you a valuable perspective on the types of information that are important to your users that can’t be readily found elsewhere.

4. Research for an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Software in the Metals Processing Industry

Our client was developing a “one-stop shop” tool to track and manage the lifespan of an order: from the initial sales process to knowing what needs to be done to fulfil the order to financials and accounting. Because this tool was to be used by everyone from the sales team to warehouse workers, we needed to observe the process end to end.

What We Did

We spent a day on-site at a metals processing warehouse, and spent time with the sales, accounting, and warehouse teams in order to follow the natural process of the tool.

While running research in the cubicles was pretty standard for our process (and something we do a lot), running ethnographic research in the warehouse presented its own set of challenges. Walking around the warehouse, of course, meant relying on paper and pens for notes. Between trucks backing up, the bandsaw behind us, and a nail gun going off in some far recesses of the warehouse, it was also hard to hear during any interviews we may be conducting. This meant that though we came prepared with session guides to make sure we knew broadly what to hone in on, the majority of our time was spent observing. We watched the warehouse workers work “as they usually do,” and asked them to go back step-by-step if we needed further insight. Again, we took 15 minutes after each session to return to the office and debrief. During these reviews, we aligned on our notes to make sure all of our researchers were hearing similar things.

Tips for Success

While observation can be a crucial part of preliminary design research, there’s nothing “normal” about having three design consultants rolling in to do watch how you work. As such, researchers don’t always get a true sense of everyday working style by observation alone. Ask questions along the way, and know that making some assumptions to fill in the blanks is okay, particularly if low on availability.

Availability can be another challenge of running research. While it’s great if we have the opportunity to observe multiple users or facilitate multiple research sessions, we usually only have a limited amount of time. In this case, preparing as much as possible in advance can set you up for success in your own ethnographic research.

5. Hospital & Other Healthcare Research

Our team has conducted ethnographic research in a number of healthcare settings including dynamic emergency rooms, as well as more static healthcare settings like sports medicine clinics.

What We Did

Working in a medical setting presents several challenges to conducting useful ethnographic research.

Aside from the obvious challenge of running research in the high-stakes, high-intensity environment of an emergency room, there were also confidentiality and HIPAA concerns in all healthcare-related environments, particularly when it came to allowing researchers to observe situations where personal health information (PHI) would be present. We were not allowed to take contextual photos and therefore relied on handwritten notes and photos of the setting minus any patients or personal information.

However, we were still able to observe products in use and gained a greater understanding of how healthcare technology and other healthcare UX services can integrate into a practitioner’s larger process and ecosystem.

Tips for Success

When working in a chaotic environment like an emergency room, you might not get the opportunity to directly interact with your users — they’re busy already and don’t need an extra distraction. Relying on observation, staying out of the way as much as possible, and asking questions only in the spare moments of downtime (or better yet, in a follow-up interview) are the best keys to success.

When dealing with information sensitive and private to your users, it’s important to be clear and upfront about what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and how the information you’re gathering is going to be used. It’s your job to get consent from your participants every time. Ask permission before recording or taking photos, and have a backup plan in case the answer is no.

• • •

Tips for Conducting Ethnographic Research

Using Ethnographic Research in Design to Inform UX

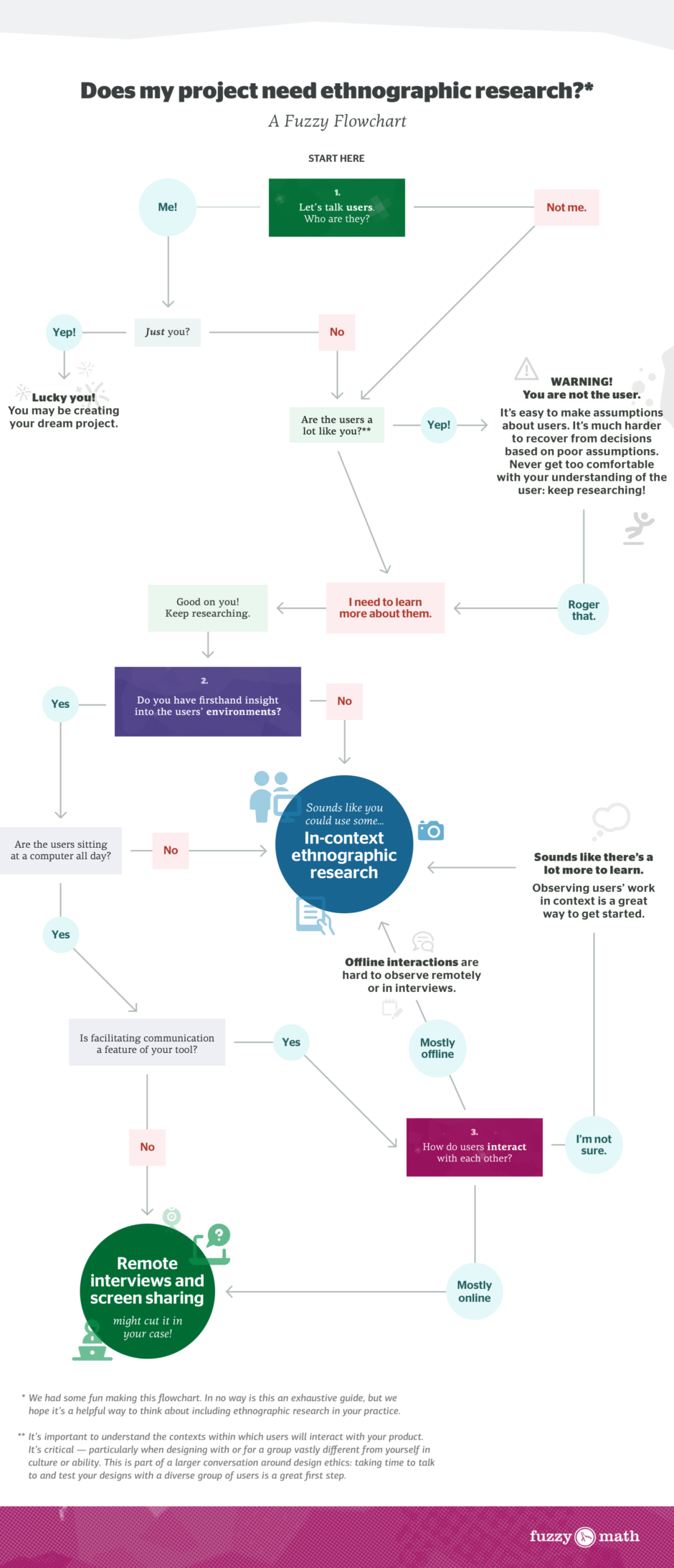

Ethnographic research in design can be done across the project life cycle, from early discovery to testing a live product in the field. But how do you decide that you need ethnography?

While location or budget constraints sometimes necessitate limiting research to a remote user interview or survey, there are a few questions you can ask yourself to determine whether or not your project is a good candidate for ethnographic research:

- Who are the users? When you’re designing with or for a group that is vastly different from yourself in culture or ability or any of a million different things, it’s important to understand the larger context of how your users will interact with the end product. Put yourself into their shoes, have more empathy. This is part of a larger conversation around design ethics that we (as designers) must be having. And while it’s, of course, best to have an inclusive group of designers working on the project, not taking the time to talk to and test your designs with the actual end users can have a disastrous effect (like this and this).

- What is their environment like? Is your user sitting at a desk doing the same task for 8 hours a day? If their process is repeatable and predictable, a screen share might be a more time- and budget-efficient way to come to the same insights. Is your user is walking around a busy warehouse? Trying to read a screen in direct sunlight? When your user is affected by a number of external forces, in-person research can give you a better understanding of the environment where your end product will be used—and the design considerations that need to be made to accommodate that environment.

- How do they interact and communicate with each other? Are they having a conversation off-line? Is someone popping their head up above their cubicle to ask a neighbor, “Have you ever run into this problem before?” and “What do I do when…”? These off-line conversations are hard to communicate during an interview or remote observation. If facilitating communication between users is a feature of your product, conducting ethnographic research may help you gain insight into how users communicate today and how they need to communicate in the future.

It comes down to having an understanding of the larger context in which your product will exist. Although interviews are incredibly valuable, sometimes you just can’t beat being there in person and seeing with your own eyes what your users are encountering on a day-to-day basis.

Strategies for Conducting Ethnographic Research in Design

Ethnographic research in design can be challenging for a variety of reasons. Some of those challenges can include:

- Fast-paced environments where you don’t get to take as many/as detailed notes or ask as many follow-up questions as you’re used to

- Consistent attention is required to capture and process information as you’re observing

- Sensory challenges such as loud background noise and/or low visibility

- Highly variable conditions, from different contexts to different use cases between individuals

- Time-limited observations that may not be able to fully capture the scenarios you want to observe, or where tasks are highly dependent on completion at a certain time

With that said, what are some strategies for doing effective ethnographic research in design?

Rely heavily on your eyes and ears.

Pay attention to conversations that people are having, comments that your participant makes, and what kinds of artifacts they have in their workspace that help them complete tasks.

When possible (and when participants will allow it), taking audio and/or video recordings of your research is helpful when you want to review what happened later. Photos can also be incredibly useful to that end.

Always be prepared.

Don’t forget the basics when prepping for your ethnographic research. Extra pens, batteries, and backup recording equipment are all good to keep handy. Make sure you have pockets or a bag to keep your backup equipment in, particularly if you might be on the move.

Be aware of your presence.

Consider the environment that you’re in and how your presence might change things from the norm. This is especially important when in environments where observation often has a negative connotation. Be clear that you are not there to judge your users’ actions or report back to management. After all, you’re there to study your users, not your users’ reactions to your presence.

Plan and schedule as much as possible in advance.

Give yourself room to figure out logistics – what you need to do, who you need to speak with, what space you need to be in, what tasks you need to observe, and what dates and times you can align all of those factors for the best insights. Determine when things are slowest or busiest, most representative, etc. and weigh your options.

Have separate sessions for contextual ethnographic research and for more traditional research interviews.

This ensures you can get in-the-moment observations as well as more reflective conversations without potential distractions. When possible, it’s ideal for each of your participants to partake in both types of sessions to give you more complete pictures of those individuals and their processes.

Prioritize your questions.

You may only get the chance to ask a few questions, so figure out which are essential and which aren’t. You may be able to rank all of your questions based on which you think will be most useful to you. You could also categorize your questions by theme and select one or two per theme that you find most pertinent.

Pair up.

The more there is going on, the more helpful a second (or third) set of eyes and ears will be. Agree on roles—one person should focus on leading the conversation, and the other should focus on notetaking.

Debrief early and debrief often.

You don’t have to wait until all of your research and interviews are done to start discussing what you’re seeing. Keep a running document of interesting or important observations you make during each session. Discuss what works well in each session and what could be improved for the next one. Figure out if you should shift your focus from one session to the next, or dive deeper into something you saw in the previous session.

• • •

Advocating for Ethnographic Research in Your Next Project

Fuzzy Math advocates for ethnographic research in design any time we hope to get insights outside of just what someone is doing on a screen — it provides more context and therefore more value than a regular interview might (though interviews are still valuable!). Despite the challenges that come with ethnographic research, we believe it provides immense value due to its contextual nature that we wouldn’t normally get otherwise. In the world of UX research, context can mean the difference between a design that feels like a natural part of the user’s workflow and one they try to avoid.