This past summer, Fuzzy Math engaged in a three-month wearable devices project, where each team member wore a device for the entire summer and captured his or her thoughts along the way. Together, we produced a set of Wearables Design Principles to guide product and design teams in the future.

Throughout this process, in multiple conversations, Fuzzy Mathletes raised doubts regarding the concept of “trust.” We were constantly questioning how much we trusted the data our devices recorded, if our data matched our perceptions of real world events, and whether or not it even mattered at all in the end.

So for a final component, a few of us took a deep dive into the notion and objective of trusting wearable data. We performed some unscientific research within the company (and on Twitter), reviewed articles and scientific studies, and came up with some ways people can design their wearable to account for the “trust” factor.

Our conclusion was thus: the data is generally not 100 percent accurate, and people don’t always trust what their devices are telling them, but these devices can still be used to effectively impact one’s life and health.

We know it’s an odd thing to say that an error-prone device can help people, but one key observation stood out. As long as the precision of the data was there, the analysis of it would be more important than the accuracy. We feel as though users only really care when the data is internally consistent and don’t care that it’s not externally sound and/or verifiable. In order words, even if it’s misrecording heart rate and miscounting steps, as long as it is recording/counting the data in the same fashion every day, it doesn’t seem to matter.

They are. They aren’t. It doesn’t matter.

The Fuzzy Math team wasn’t alone in wondering just how much people trusted the data their wearables collected — and if the accuracy of that data even mattered. In fact, a handful of scientific (and not so scientific) studies have been done to determine just how accurate wearables are, and it seems the jury is still out.

A team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania set out to determine just how accurate a handful of the current wearable devices on the market actually are. In their research, they looked at five of the current devices out on the market. While tracking participants across 500- and 1,500-step trials, they found that the wearables in their study were under-counting users’ steps by anywhere between two and 23 percent. Smartphones, on the other hand, were counting seven percent less to six percent more steps. At the end of the day, they determined that smartphones were more accurate than most of the wearable devices available today.

Not to be outdone by the team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, a team over at Wired performed their own independent testing of wearable devices and smartphones to answer for themselves which was most accurate. Aside from their claim that tracking steps really isn’t the best way to track health, the Wired study found that the wrist is where it’s at. When tracking 1,000 steps, they found that the smartphones were under-counting steps from anywhere between 0.5 and 8.6 percent. The wearables, on the other hand, were found to be over-counting, but were more accurate.

The Wall Street Journal takes a stance similar to the Fuzzy Math team after our wearable experience this summer. Ultimately, even if the wearable device is collecting inaccurate data — but doing so consistently — users will benefit from it. Illustrating the same point from the Wired article, we feel there are significant limitations based on activity type in addition to the device being used to track the activity.

Unscientific Research

Throughout the course of our wearables project this summer, there was a lot of discussion around the accuracy of the data our wearable devices collected and whether or not people trusted the data from their wearables. To learn more about how wearables data influenced people’s trust, motivation, and behavior, we decided to conduct some quick, informal research.

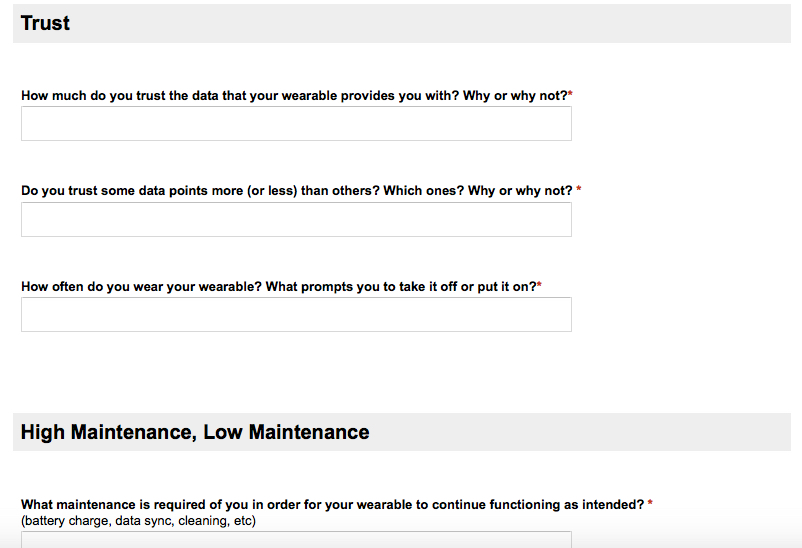

We conducted two surveys — one survey was internal for Fuzzy Math and had several open-ended questions around trust, motivation, behavior, and maintenance involved with our wearables.

The other survey was a single question posed multiple times a day for one week via @FuzzyMath on Twitter: “Do you believe your wearable’s data is accurate? Favorite = YES, Retweet = NO.”

The outcome of the responses from both surveys was highly varied, but was weighted towards skepticism and general belief that wearable data was not accurate. However, we also found that participants didn’t always tie the accuracy of the data to whether or not they liked their particular wearable device. In some cases, we even found that despite beliefs that the data was inaccurate, participants still trusted their wearable device.

With what we heard from our small sample size, we’ve drawn a few conclusions regarding the relationship between users and their wearable data:

- People had greater motivation resulting from their wearable device if they believed their device’s data was accurate (or at least within the ballpark). In these cases, just wearing the device seemed to be enough to cause behavior change; it didn’t matter if the data was highly accurate or if the user even looked at the data.

- People who believed their wearables to be extremely inaccurate were not motivated by their wearables and were instead frustrated by the data provided. These folks tended not to like their devices at all.

- Regardless of whether people liked their device or not, they agreed the individual data points weren’t as important to them as comparing summary data over time.

- People thought their wearable devices should give more guidance to support what the data means for them, as well as how to change behavior according to the data provided. It didn’t particularly matter if the data was accurate.

- People felt that feedback from their device should be more instantaneous, or at least more accessible. In some cases, there were many hurdles people had to jump over in order to access the data they needed in real time.

Conclusion

After wearing our devices for three months, reading a handful of scientific and not-so-scientific articles, and conducting our own (not-so-scientific) research, we feel confident in saying that the data from wearable devices probably isn’t all that trustworthy, but we’re just as confident in saying that untrustworthy data is A-OK, as long as all captured data is equally untrustworthy.

That might seem a bit odd to read — it’s definitely a bit odd to write — but our personal feelings towards our devices, the research we were able to track down, and the research we completed all led us to this conclusion. As long as we can tell, we’ve been walking more this month than we were three months ago, sleeping longer now than we were then, and even handling stress a bit better than we were at this time last year, so we’re happy customers when it comes to our wearable devices of choice.

This wasn’t quite where we all expected to land when we set out on this journey at the beginning of the summer; here we find ourselves in a newfangled, intriguing-yet-satisfying place where data trends rule and individual data points drool. If there were ever to be a Fuzzy Math wearable device [editor’s note: there won’t be], we would approach it with the following gained insights in mind:

- Ensure that captured data is close enough to reality to be believably accurate, but note: perfect data wouldn’t be our goal.

- Expose how we’re capturing the data so there’s no confusion or frustration with the data presented.

- Distill what the data means to the user by highlighting trends: compare newly captured data to previously captured data, and highlight insights into what all that data means.

- Utilize personal connections of friends and relatives to ground users’ data in context against others’ data (and always — always!— give the user full control and clear insight into who can view which data)

- Focus aspects of the device and supporting apps around health goals, and use elements of gamification to get there.